Visual Arts Facsimile

Thursday, April 1st, 2010

In 1973, the Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM) in Mexico City launched the magazine Artes Visuales. The magazine was one of the museum projects of the ever-dynamic Fernando Gamboa, MAM’s director from 1972 to 1981. During his lifetime, and through and beyond his work at MAM, Gamboa became a leading exhibition designer and organizer, museums director, arts promoter, as well as prominent figure in all matters relating to cultural politics in this country. His work is recognized for its attempts to present a “modern” Mexico to the world.

This year, MAM published an anthology of Artes Visuales compiling selected pages in facsimile of each of its issues, and including a forward by Josefa Ortega and an essay by Carla Stellweg, collaborator of Gamboa and co-founder end editor of the magazine. The book is released in conjunction to MAM’s current exhibition Fernando Gamboa: La utopía moderna. Curated by Ana Elena Mallet, the exhibition explores Gamboa’s work as exhibition maker, cultural politician and arts institution builder at large.

In the book’s Documenting the Undocumented, Carla Stellweg narrates the story of Artes Visuales. I take particular interest in her text, for beyond being a personal essay that describes the inspirations and history of the magazine, it takes the writing style of storytelling to anecdotally account a particular arts scene in Mexico during the 1960s and 1970s, and a little written-about, even seldom discussed, cultural institutional history of the time. Stellweg cites influential projects to the making and emergence of Artes Visuales, including The Counter Biennial (1971), a book of Museo de Independencia Cultural Latinoamericana, known as the project MICLA; the New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition and catalog Information (1970); and Mexico’s Taller de la Grafica Popular (founded 1937).

Stellweg openly states in her essay how Artes Visuales was tied to a political ideology beyond (and, perhaps, also through) the curatorial program of the state-run and publicly funded MAM. It was discursively part of larger cultural project of Mexico’s 1970-1976 President, Luis Echeverria, which she describes as being rooted in “a return to the democratic ideals of basic human rights and freedom of expression…” and a call to “intellectuals who had left Mexico in 1968 to return and be part of a reconstruction process.” Echeverria was recently prosecuted for the Tlatelolclo massacre of 1968, and other similar events and insurrections that led to killings while he served in the cabinet of the presidency before him and during his own. Notwithstanding, Stellweg acknowledges this, and that relating Artes Visuales with his governance is a tricky subject to address, yet, I should add, necessary for mapping public projects and their structures.

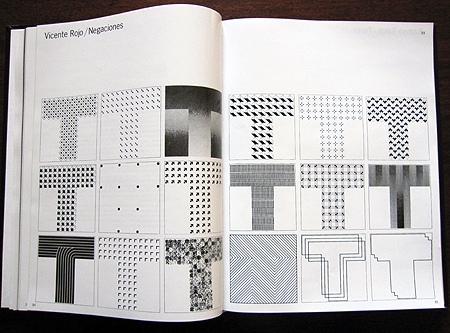

The image above is part of Vicente Rojo’s contribution for issue six of Artes Visuales (June 1975), guest-edited by Salvador Elizondo, and reprinted as facsimile in the new anthology of the same title published in 2010 by Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. This issue was project-based, and approached the use of image, text and typeface in concrete poetry and contemporary art of that time. The visual artist Vicente Rojo collaborated as graphic designer of Artes Visuales.