Raising the paddle for a surrealist manifesto and a 1990s painting on Melrose

Tuesday, May 20th, 2008

Andre Breton’s original 21-page manuscript of the Surrealist Manifesto (1924) will be auctioned tomorrow afternoon at Sotheby’s in Paris. This historical document is part of a larger auction including more than 200 lots, items drawn from the collection of Simone Collinet, Breton’s first wife. (Collinet died in 1980; the sale is arranged by her heirs.) The collection includes books, photographs and manuscripts, among them nine in Breton’s handwriting. There are other gems in the collection of documents, too, such as a manuscript of Les Soeurs Vatard by Huysmans, a series of written and typed and noted manuscripts, tapes and correspondence by Simone de Beauvoir, and a handwritten letter, Souvenirs de la Commune, by Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon). There is so much more. How crucial it is to see the handwriting, the strikethroughs and additions marked in the editing, the margins. This is the texture of the words and ideas of these texts.

These and other items of the collection were part of the five-day exhibition, Surrealism in Paris, at Sotheby’s Galerie Charpentier in Paris, which I went to see before their auction tomorrow afternoon. (An exhibition of these documents was also presented in Sotheby’s London in January-February 2008.) It would take time, I thought, for these original documents to be on view again. After their auction, these will most likely be shipped away and kept in the backroom of a national museum, the restoration lab of some institution located in a California hilltop or at a climate control storage in a suburb somewhere in the world.

Where will be the home of Breton’s manuscript and these other items? It’s unclear. And, why wouldn’t the family just donate them to a national museum here in Paris, where the manuscript was drafted and the movement conceived? I forget common sense is just a myth.

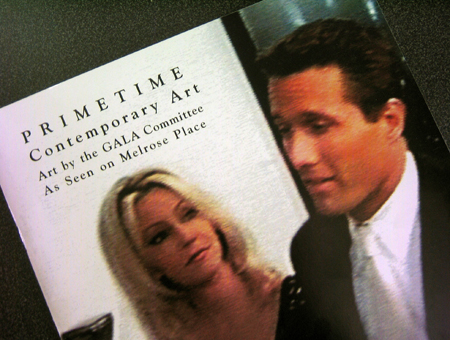

The idea of uncommon sense crossed my mind, and suddenly the GALA Committee auction at Christie’s a decade ago invaded my thoughts. Held at Christie’s in Beverly Hills on November 12, 1998, Primetime Contemporary Art. Art by the GALA Committee As Seen on Melrose Place brought together 49 lots for live auction and 51 more at silent auction. These 100 lots were GALA Committee artworks created for and appearing in different episodes of the popular television program of the time, Melrose Place. No need for me to summarize such a multi-layered art project and event. Instead, I here transcribe the catalog’s introduction, written by Brent Zerger (who, at the time, worked in LA MoCA’s now-defunct department of experimental programs headed by curator Julie Lazar):

In The Name of the Place is a complex collaborative project by the GALA Committee, initiated by artist Mel Chin for the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (LA MoCA). Working with the Uncommon Sense theme of public interaction, the GALA Committee selected a prime TV program, Melrose Place, as the site for creative a massive “condition of collaboration” among an array of individuals, institutions and interests, organized initially around the activity of developing and placing site-specific art objects on the program’s sets. During the two-season interaction, the art-enhanced weekly broadcast reached millions internationally. Radically expansive in form, with diverse aesthetics and a wide range of audience/artist television production involvement, In The Name of the Place is an experiment that illuminates unexplored, creative territory at the intersection of museums, mass media and artistic action.

The culmination of the project is the public auction of the collectively-made art works. All proceeds from the auction will go to two non-profit educational organizations, the Fulfillment Fund and the Jeannette Rankin Foundation, to be used specifically to benefit women’s education.

The GALA Committee artworks were sometimes props—like, bed sheets with print design depicting condoms and promoting safe sex; Chinese Take Away paper-containers with inscriptions of human rights messages; a paperback book of Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy. At other times, the artworks were also just that, paintings hanging on walls and sculptures over pedestals. The closest meeting point between Melrose Place and GALA Committee’s collaboration was shown in a 1997 television episode with a scene happening at LA MoCA’s Geffen Contemporary. The actual set is the exhibition Uncommon Sense. For this, the program’s screenwriters wrote a scene in an art show and the producers commissioned GALA Committee a painting that would be discussed by two characters. (See image above for a video still, as reproduced in the auction’s catalog.) Not coincidently, the painting is titled Fireflies –The Bombing of Baghdad (acrylic on canvas; 72 x 96 inches) and shows a night scene apparently inspired in style by artists like Vija Celmins and Ross Bleckner, and in subject by the controversial televised US bombings of Iraq during the 1990s. (A month after the auction, the US conducted Operation Desert Fox.)

Aside from LA MoCA, and before this auction, the artworks created by GALA Committee for this project were exhibited at the Kwangju International Biennale in South Korea; Grand Arts in Kansas City, MO; and Lawing Gallery in Houston, TX. For the Grand Arts exhibition, curator and art critic Joshua Decter—who pointed me to this project in 2002, while we were planning a round table discussion about artists working in television—wrote a text detailing the collaborative process of GALA Committee with Melrose Place. More recently, Art:21 produced a documentary about Mel Chin, wherein the project is also discussed.

The Carsey-Wolf Center for Film, Television, and New Media at UC San Barbara hosts the excellent web-archive of GALA Committee’s In the Name of a Place. The site, which states is still development but looks slightly dated, gives a sense of some artworks and their provenance—what “made it,” as they say, in the television show. The catalog of the Christie’s auction, which part of the cover illustrates this entry, remains more comprehensive in so far it illustrates the variety of artworks produced for the television show. It lists all the members of the GALA Committee, additional information of the auction, and images and provenance of the 100 artworks at auction, with captions describing the context that inspired the work or the scene in which it was placed. And then there is a funny inclusion: the catalog’s last page includes an unsigned text dated 2021 about GALA Committee’s so-called non-commercial product insertion manifestations (also included in the project’s web-archive).

Today, I wonder, where are the homes of these series of artworks by the GALA Committees? Where does the pool game item Africa is the Eight Ball sit or the landscape painting Rodney King hang? What kinds of collections are they part of? And, how are these artworks displayed to retell, or not, of their original context and presentation?