Bermuda Triangle

Friday, March 15th, 2013

Already two hours of turbulence, and the only thing he’s thought about is drinking a cup of coffee. Take a seat, sir, the stewardess demands, with a voice so deep that rhymes with her heavy-custard lashes.

They’re flying over the Bermuda Triangle, and he thinks of being gobbled up by the sea, taken by extraterrestrials, seduced by paranormal activity. He concocts scenarios for these potential disappearances, but his more pressing craving, coffee, interrupts these attempts at narrative. If he would only be served a cup, he could be more concentrated.

The scene is of a modern orchestra in full performance, with an audience horrified by the uproar of its wind instruments. He can perceive the smell of vomit increasing. The drama. And now, aside from longing the aroma of fresh ground coffee, he yearns the scent of Brazilian Paprika… that perfume nestled in a miniature khaki-tweed bag packed in his carry-on, the fragrance he wears when he is in fact not in Brazil, a mnemonic device, Proustian madeleine, for his life there.

He only gets goose bumps when, at every jolt of the plane, his one aisle mate clings her nails on his arm; experiences dizziness by his other aisle-mate’s constant air tracing of the sign of the cross. Perhaps some coffee could induce in him a more appropriate level of anxiety, you know, to be more attuned to the spirit of the flight.

His calm body is sandwiched between these two nerve wrecks: one who’s probably never had a grip on life; the other who may have over-done it, confusing her religious ritual with air marshalling, wanting to guide something—this flight, the weather, their mortality—that she, that he, that all there, bound to seatbelts, wont ultimately get, at least this time around. Come on, one can’t even get a cup of coffee.

A ding-dong ring-tone marks survival. The aircraft has stabilized. The window shades are slowly lifted, and the light-blue hue of a clear sky illuminates the interior of the bird. Passengers slowly fall asleep from exhaustion, from their preceding edgy mood. There’s mostly silence, except for the stewards’ usher, their drink carts march. Coffee, sir? , she offers him. No, thank you, he replies decidedly, I’d actually prefer the drink pictured here.

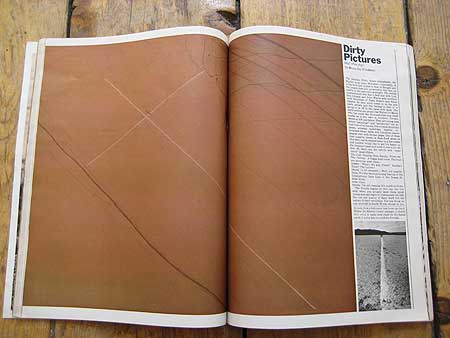

Image: The June 11, 2007 magazine issue of The New Yorker, showing “Roy Spivey,” a short story by Miranda July illustrated with a photograph by William Eggleston.