Nevada on my mind, land art you are so kind

Sunday, July 27th, 2008

What is it about aerial photography that makes plain land so extraordinary, so marvelous? Is it the unusual perspective of something so familiar called the world? Is it the abstractness of it all? Aerial photography reminds me of how much there is to see, how much more there is to experience. No need for a hilltop or penthouse, to see a shot of these a day will do.

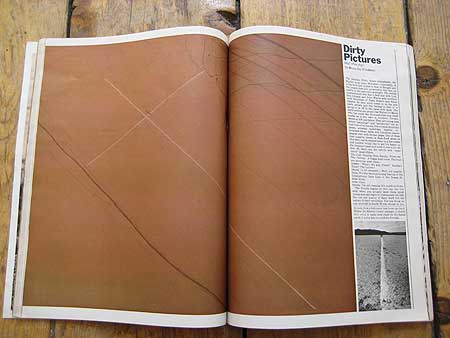

Footnote #1 – I took this photograph some days ago at the studio of the Parisian artist Pierre Leguillon. It is of a page-spread in an early-1970s issue of Harpers Bazaar. In this magazine issue is an image Pierre is working with for an art project—one of the best I’ve seen to date—and just pages behind it is a feature article by Bruce Jay Friedman on earth art, a new form of art making for that time. The earthwork figured is by Walter de Maria.

Footnote #2 – In a way, it was by coincidence that I got to this image. This encounter triggered a wonderful imaginary trip that passed through recollections of other stories and impressions far from the magazine until finally hitting a place: this image was so close to a satellite picture showing the abandoned and mysterious landing strip that inspired the recent construction of the International Airport Montello (IAM) by the artist’s group called eteam. Like de Maria’s chalk earthwork, eteam’s IAM is in Nevada. Can this image clue us into the history of the IAM airstrip?

Footnote #3 – Almost two years ago, I visited Michael Heizer’s Double Negative. Its monumentality is impressive. Its arrogance of form yet appropriateness to place is breathtaking. The visit there was part of a longer art-trip made with a group of colleagues and friends, all of who had experienced a flight-layover the day before at eteam’s IAM. And there, on that Sunday afternoon at the side of Double Negative, which is in the middle of nowhere, was The Independent British art critic Charles Darwent. He was on a road-trip across the American southwest on a self-designed Land Art tour. His article is published here, and is a great travel-guide and resource for that kind of trip.

Footnote #4 – Minutes after having published this entry, eteam sent me a note pointing out that this very day The New York Times published a review of the novelesque Spiral Jetta. A Road Trip Through the Land Art of the American West by Erin Hogan. The review is written by Tom Vanderbilt, one of today’s most adventurous and imaginative writers on culture. He is uthor of Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What it Says About Us), released this month, and Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America (2002), among other books and articles. Some years ago, Tom also wrote about his layover experience at eteam’s IAM. That piece was published in Modern Painters.