For you, the common cold is simply uncommon; influenza is far from influencing; a stomachache is more an urban myth than a sharp pain; infection is a synonym of inspiration; virus is something that attacks computers; disease, an invention of antiquity somewhat controlled by modernity; epidemics, a subgenre of apocalyptic fiction; depression and its variations, barometers of cultural tolerance and measure of institutional mores at a given place and time.

Not that you fully embrace these conjectures. These just happen to be the ways that you’ve experienced these maladies.

Sickness is a rarity, your very-seldom visitor. And as you take a drag of your cigarette, you recognize that its paucity is not exactly because you’re a health nut. Wellbeing has simply been around. Most probably, the blessed absence of sickness is a matter of luck. Okay, maybe it’s also because you were raised in a polluted part of the World, where you came naturally into touch and no later immune to most germs.

Ay, but when sickness does strike, its visit is pitiless and dwelling bizarre. It afflicts your major senses.

Something happens in an eye, momentarily blinding you. A next to nothing upsets an ear, briefly leaving you deaf. A thing grows in your vocal cords, provisionally muting you. Exhaustion the plausible source of these ailments, your body goes on strike—telling you it’s seen enough, heard enough, talked enough. Your senses literally shut down. Keep you still. That makes you ill. Handicapped. Guarded yet defenseless. Surrendered to surgeons, their treatments, operations and machines.

This is when an absolute faith in abstract-Others and a strong belief in technology take over your body. Prayers are implored. Antibiotics welcomed. Holistic cures practiced. Witchcraft performed. You’ve tried it all. It’s worked. However, none of this remedies what’s currently affecting you.

This time, for the first time, it’s your sense of intuition that’s uneasy. You get seasick at the sight of a fountain. You’ve often forgotten to wear your Teflon suit. You’re vulnerable. Suspicion is a breath away from awareness. Feeling more than enough. And, you’re overdoing it, the sense of intuition tells you, making it work extra time in that very insinuation.

For once, you’ve fortunately identified the signs before the crash. Some symptoms are evident. The right side of your head spools white hair. A fault line deepens between the eyebrows. The upper part of an ear blushes. Some other symptoms are invisible. The muscle behind the breastbone pulsates unsteadily. Blood heats. A certain aspect of the metabolism accelerates.

You point these indicators to others, to see if they notice, to brainstorm causes, to recommend antidotes. People tell you not to worry. Your friends say we’re only getting older. Your family says that it’s life, intensely lived. Your colleagues say that it’s stress. They all suggest vacationing. Your stylist advises dyeing your hair; your yoga instructor to hold your pose longer; your psychoanalyst to increase the frequency of meetings. Your doctor gives you probiotics and creams.

You truly find all this hackneyed. You feel you didn’t explain your debility just right or that they simply, palpably made a wrong diagnosis. You wonder if this is because pain doesn’t ensue with this sickness (and if it does, you’re body is too tolerant to acknowledge it, externalize it), and without that apparent sign, whatever noticeable proof of your condition goes undermined.

Ugh, for that very thought, your instincts were beseeched. Yet again, your sense of intuition put to work.

All the while, the sense of intuition’s boycott seems impending, and you’ve decided to pre-empt that. You’ll come to terms. The sense of intuition is your dearest. You need it more than anything. Want it. You trust it. You know it’s irreplaceable. There’s no natural prosthesis for it, and artificial intelligence is not significantly advanced to rely on. Besides, you know your body best. You must act, and you have a hunch that resistance is an essential characteristic of that very action.

The self-prescribed, preventive cure you’ve concocted: to shift decision making from the right to the left side of the brain. Better for melanin to decrease from that part of the head, you think, and just like that, you deduce that it’s best to logically address certain matters. Most. If only transitorily. You want your sense of intuition at the forefront, except you deem it’s vital to leave it resting and healing for a bit. You’ve rationalized this. It agrees. Finds ease.

The challenge of the treatment will be how to avoid the wrought belief of common sense supplanting the sense of intuition. And you prepare to tackle this.

You purchase Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor. Download all Lispector’s novels. Dive in Laguna’s poems. You frequent cafés named Barbarella, Alto Astral, and the cosmic like. You even make time for solitude at the ever-barest Everest. You take up a new language, and in that infantilizing learning-process you cling onto basic words, forget complexity, and disregard enunciation, that is, intent, because, fact is, you’re unable to fully grasp it… for now. You think.

You study Cancer, not your horoscope, but the disease that has assaulted close friends, that tough course on empathy that you’ve skipped. You address the signs of aging in loved ones, that stage of filtering memories, that questionable argument for deskilling, the hardest class on compassion. These sicknesses that have (up to this point) only presented themselves as lessons in life, some of which you’ve clearly flunked before, will be tried again.

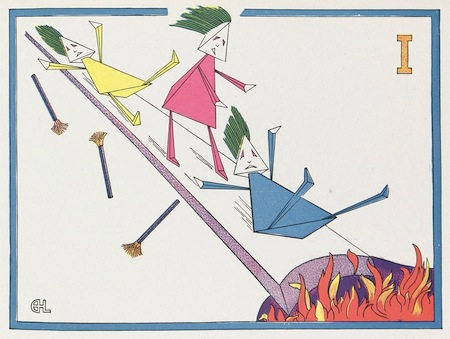

Image: “I’s for the Cubies’ Immense Intuition” from The Cubies’ A B C by Mary Mills Lyall and Earl Harvey Lyall (USA: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1913), drawn from 50watts.com after Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, and landing here via Mario Garcia Torres.