Why I Always Cry on Airplanes

Friday, September 14th, 2012

I was unsure of leaving this entry’s title in first-person. Was also unsure of how and if I should punctuate it—to end it with ellipsis, as in here goes the list of reasons, or to add a do before the I and end it with a question mark, as in I am bewildered.

Point is: I always do cry during air flights. It seldom happens before take-off or landing, so no need to associate it with fear of flying. It actually tends to happen mostly after an hour or so on air. Sometimes tears just begin rolling down. Other times tears are announced by a knot on the throat or accompanied by some indeterminate muscular pain. Few times there’s actual weeping, and I am unsure if it’s because these are tears of exhaustion or of measured emotion. For sure, never are these alligator tears.

I’ve decided to wear prescription sunglasses during flights to avoid exhibition. Reddened sinus effects, blush cheeks, and slightly swollen lips rarely manifest. Though parallel and occasional teardrops from the nose are inevitable. The uncertainty of these discrete waterfalls prompts me to push the orange-button on the seat dashboard. Once the steward arrives, I request a tissue, then some bubbles, and if possible, I add to my request, to serve them on a crystal glass rather than a plastic cup. Sunrays or stars are hidden from the aisle seat—my preferred area on-board—so seeing sparkles on a glass and feeling them down my throat always trigger the experience of moving in a landscape, of being grounded yet on air.

From the explanations available online, the reason for my tears is probably because I fly coach, unfortunately. According to recurring travelers and pseudo-scientists that populate the Web, oxygen is limited in the back of airplanes, making those people seated in economy more sensitive, teary, as they say, during flights. That theory, however, is mostly associated to crying while watching movies on planes, specifically romantic comedies and generally-tasteless Hollywood melodramas on airline repertoires, which, to me, this only means that films on planes (should I add tears here?) cannot be taken all too seriously. In any case, that popular theory would not reason my tears, as I tend to read or dream on flights.

It’s unclear when this started happening, the crying. I barely noticed them last year or so. When the tears actually settled into ritual was just some months ago. As of late, it is their appearance of comfort, their I am here to stay while on air, that has become somewhat preoccupying, sometimes even more daunting than the tears themselves. And so, I’ve begun wondering if crying is because I am leaving a place—my home, or a place that feels like it, or a space that could be that should I had stayed. I’ve also wondered the opposite, if crying is because of having to go back home, or to a place that feels like it, or to a space that could be that someday.

Whether it is the sense of impending arrival or the acknowledgment of a departure, I’ve begun coming to terms with tears and some day will do so with the idea of home—whatever or wherever that is.

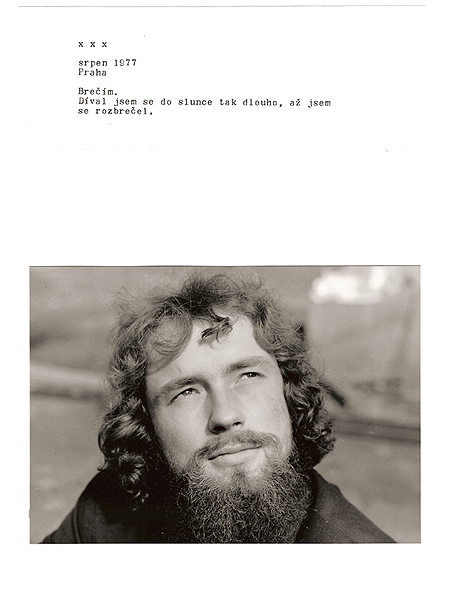

Image: detail of Dear Mr. _____ (from a desert to a mountain to a waterfall), 2012, by Tania Perez Cordova.