Show and Tell

Wednesday, October 1st, 2008

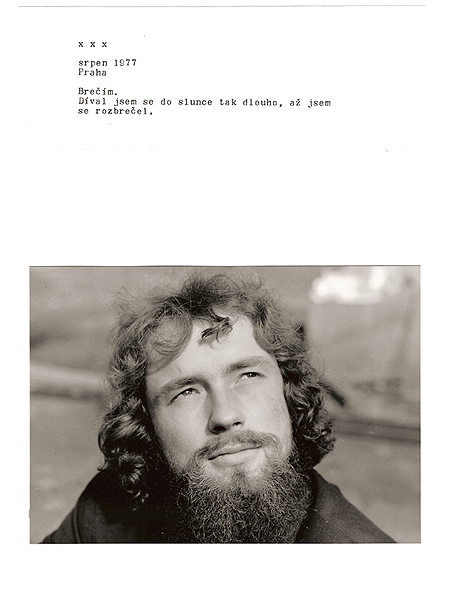

I went to kiss Jiří Kovanda at Bétonsalon—a re-enactment for him, first time for me. The kissing was one of the performances in Playtime, an exhibition curated by Bétonsalon’s director, Mélanie Bouteloup, and her colleague Grégory Castéra. In different ways, the curators played with the notion of performative display, redefining the use of the gallery, shaping roles for its staff, and orchestrating audience participation. In seeming complicity with the artists, the curators chose to leave the gallery pretty much empty, and instead exhibited, performed, or activated the artworks in different modalities and times. Some artworks were installed in closets and office areas. Others comprised audio works that played in portable CD players with headphones or were scheduled activities. Some others were listed in a checklist and shown upon request. I enjoyed this last modality the most, and here I briefly recount it.

Following the scholastic model of “show and tell,” in which a personal object is the starting point of a demonstrative conversation, a gallery attendant at Bétonsalon escorted me and a couple of others to a table with seating, where he calmly presented a series of images, books, and objects that he had drawn from a closet. He began his “show and tell” by talking about his outfit. A slim young man, he was wearing a sparkling white Adidas jump suit that accentuated his cool and relaxed demeanor. “It’s an artwork by Ryan Gander,” he explained, while pointing out an embroidered red stain the size of a bullet-hole located on his jacket roughly near his belly. Wearing matching gloves, our artwork-dressed interlocutor presented each artwork with calm self-assurance. This is this, and this is that, he said. He spent about five to ten minutes talking about each thing, concluding each factual presentation with a personal viewpoint or interpretation.

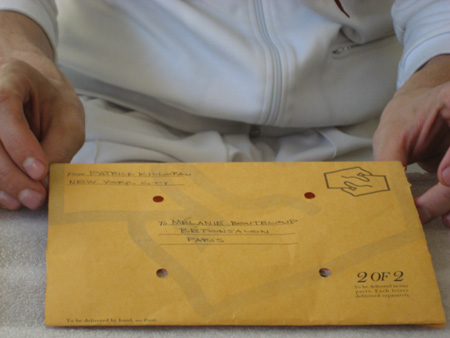

When the time came for what looked like a standard manila envelope but which was, in fact, a carefully designed and crafted package, the attendant removed his gloves to handle the piece. It was an artwork by Patrick Killoran, one in a series titled “Hand to Hand,” that like its title suggested a mail artwork that circumvents postal service. Betting on suggestion and affiliation rather than on addresses or the other usual postal types of information, each package was prepared in two sets and sent out into the world simultaneously. Before it reached its addressee, in time for the exhibition, the first envelope had only passed through the hands of a couple of people. The second one, however, which I confess passed through my hands, here in Paris, but was a day later held by someone else in London—had yet to arrive to its intended recipient at Bétonsalon. (Signatures and locations of couriers were chronologically listed in a form on the back of the envelope.) This time, our interlocutor saved his opinion and took it upon himself to be the messenger of the travel anecdote of its deliverer. It was a meta-conversation about delivery, if you will. And just when he was about to put the envelope aside to pick up the next work, a woman next to me interrupted him with: “So, what’s inside?” Our attendant, responding playfully with an “I don’t know,” opened the envelope to start another round of “show and tell.”